What makes one go outside and scream?

Shorties 5

This is the fifth installment of Shorties, a series where I review a short book off my shelf each week for ten weeks. An archive of the previous installments can be found here. Next week I will read and write about a book as yet unknown to me.

The Activist by Renee Gladman. Krupskaya, 2003. 145 pages.

In the late 2010s I was in college, where questions of identity and truth and power were swirling around so tangibly I could basically reach out and grab ideas and put them places. Among those ideas was one about truth—whether or not we were living in a time beyond it. My mentor wrote a book called The Work of Literature in an age of Post-Truth and I indexed it.

Of the ideas that dominated my life at that time, I registered this question of un-truth as the least interesting and useful. I was busy thinking about race and gender, where truth came up aslant with preference, with social construction. Questioning markers of identity and their social use was a way to talk about social mandates more generally; the issue of whether or not the government, the media, or anyone else was changing the meaning of “truth” itself seemed passé, and like something that people who refused to spell Trump’s name properly, or called him only “the Orange Man,” would care about. In short, this was an issue for neoliberals to fret over, and I was not one of them.

I’m not sure that the issue of whether we live in a post-truth society matters to me more these days, but I do care much more about what narratives do in the world, how and where narratives are constructed. This is partly because I care a lot now to think about where craft appears in reality and to what degree what I’m experiencing linguistic sleight of hand when I read something. It’s also because I taught one semester of nonfiction writing to classes of newbie writers, who on the whole seemed concerned about what it meant to write nonfiction with a fixed (relatively small) amount of life experience. In this way we were essentially the same: I also did not know how to write nonfiction with the amount of life experience I had and also wondered every single day about what it meant to write honestly.

In The Activist, a small group of political insurgents are planning their next major action in the midst of apparent unrest. But the map they’re using changes before their eyes. A bridge either has or has not been bombed, depending on who you ask— the government says the bridge is in ruins, backed up by experts from Canada. The commuters who use the bridge every day can see clear as day that it is not damaged, and stage protests to reopen it; when asked about their organizing leader, they name a missing, maybe nonexistent man.

The book—written alternatingly in verse and short vignettes that read like reportage—deals in themes of communication and solidarity, collectivity and protest. Characters move as if through dreams, and a reader jumps from inner monologues to covert meetings, from the perspective of a “sympathetic” reporter at a protest to an activist lying in tall grass.

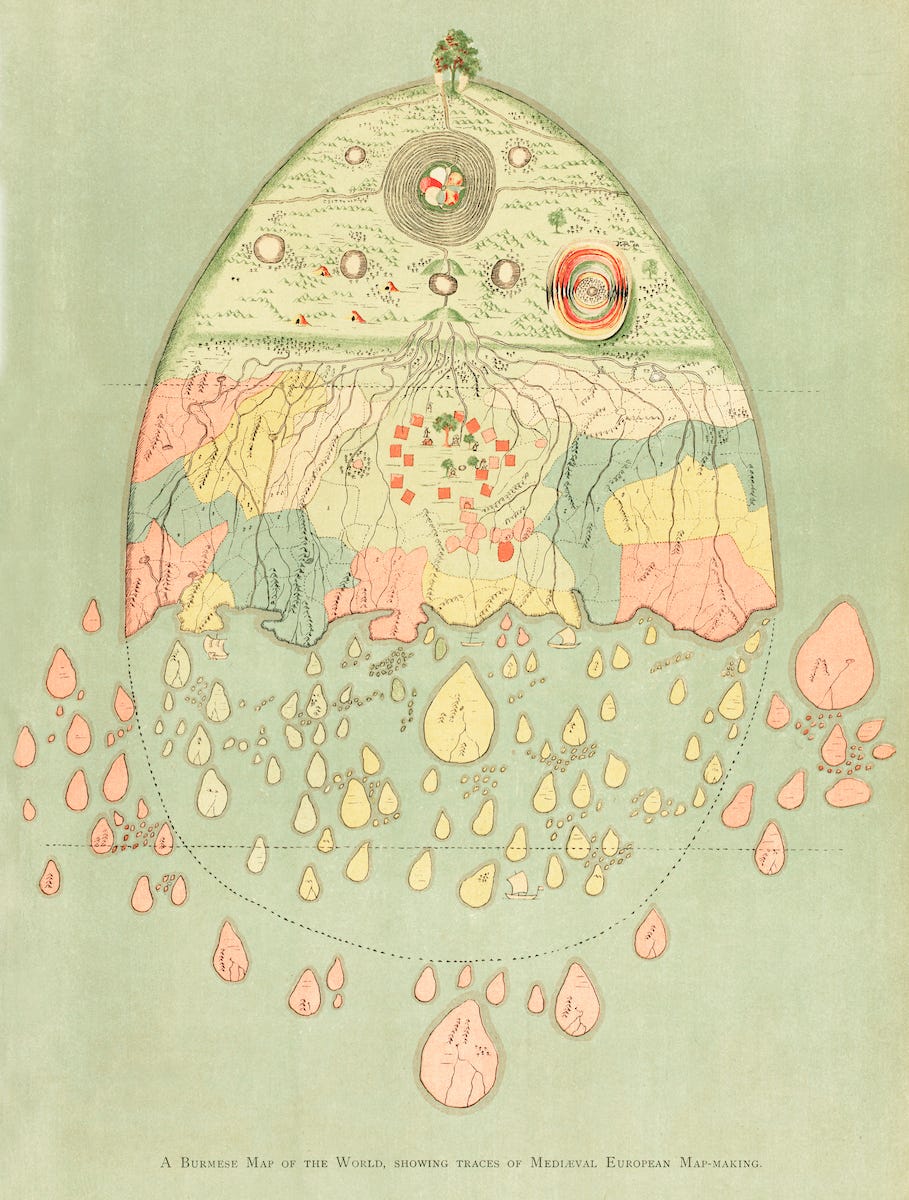

Crucially, it’s also about mapping. To map is to document; to document is to remember in subjective terms. In The Activist, mapping is a shifty medium, one that has the potential to conceal a threat and to undo lines of communication. As the insurgents prepare their next action, the map they use fails them—streets change or disappear from the page—but none of them can easily communicate with one another what’s happening. Finally, one of the activists gets through to another with a note that reads “I’ve seen the map mutate too. Let’s meet later.” When the two finally meet, they can only say a few words to one another:

Why is the map mutating?

I don’t know.

Then a half hour of silence.

What does it mean to rely on a map that someone else has drawn for you, even to make plans which subvert those who have written it? Even the sympathetic reporter works in this continuum. (Audre Lorde: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”1) The problem comes not only in the faulty tools, but in the breaking down of communication that ensues among the activists, who speak in code languages across multiple groups, love each other, but cannot, on some basic level, get through to one another.

The maps and the reporter were my fixations reading this brief book for two respective reasons: my familiarity with Gladman’s more recent work, and my proximity to reportage in my working life. I first learned of Gladman through Plans for Sentences, published by Wave Books in 2022 and quite a different type of book from The Activist. Plans is a book of drawings and text—the line drawings inform the text, which describes what the sentences will carry out or might do. In a sense, these line-texts can be understood as maps, drawing the connections between language and line, and creating an architecture of Gladman’s poetic sense.

It’s fun to imagine that one has found a writer’s fixation, the thing that they cannot help but return to, so I’m choosing to believe that for Gladman I’ve found that thing, and that it is maps. The other, perhaps clearer, connection between these books is their separate explorations of how to communicate through language what we feel, think, see, and believe. Gladman is wondering in both of these books how words work in a tangible or intangible way in the world. It just so happens that she’s also thinking about lines, the foundational element of every map. To what extent are poems, words, all language, just maps in a different format?

The book opens with and later returns to the perspective of a reporter, who from a protest describes their work as wanting to “get to the bottom of things—as in any archaeological work.” But very early in the book they say something that directly contradicts this idea:

Standing here, doing nothing, I realize the problem with the activists. They are covert, and when you are covert, you miss out on the best information.

Everything one needs to know is right out in the open.

I have nothing illuminating to say about reporting or journalism, only questions about veracity and creating a narrative that could at any point become tools for someone else (the state, the activists). It’s something I’ve turned over a lot in the past few days, as I’ve watched news of the flooding in Central Texas unfold primarily in my work Slack and in a group text with my mom and my sister. In these channels, what was true was practically unverifiable—cell service was scant, no one was getting in or out, and the extent of the destruction and fatality of the floods continually grew. But the news was horrible, and so personal that much of the time it felt wrong to know it so soon, before it had broken elsewhere. The flooding which swept away the girls’ camp, Camp Mystic, happened down the way from where me and my sister spent our summers growing up, where plenty of families we know vacation, and where friends and acquaintances sent their own children to camp, some of them this year. Where I might consider myself an outsider to true Texan culture, my workplace (a Texas magazine) is full of writers and editors who are completely of this place. It’s clear that most of us have lost count of the amount of people we know who were affected by the flooding.

But the work! It must be done. Staffers were in the Hill Country by the next morning to do their work; by the afternoon, many of them were evacuating out of caution over a potential second wave of floods. What we say now and in the coming months—these things will become, in part, the history of this time. This is obvious, an essential quality of journalism, good or bad. Nonetheless it gives me pause.

I can appreciate that The Activist’s reporter is so willing to contradict themself. Or maybe they are simply describing the act of narrativization in two parts, two sides of the coin: to see what things for what they are and as they appear, and also to know that some truths must be dug out from below the surface. 🐁

Even the mention of this essay should be a footnote, tangential as it ultimately is. For those who are interested, you can read it in full here.