One Body Problem

Shorties 6

This is the sixth installment of Shorties, a series where I review a short book off my shelf each week for ten weeks. An archive of the previous installments can be found here. Next week I will read and write about The End of the Story by Lydia Davis.

More, Please: On Food, Fat, Bingeing, Longing, and the Lust for “Enough” by Emma Specter. HarperCollins, 2024. 208 pages.

In her essay “Against Ordinary Language: The Language of the Body,” Kathy Acker—known for her provocative, avant-garde fiction—is attempting to describe her experience of bodybuilding, a habit she’s cultivated for a decade by her time of writing. But from the jump she admits that she has tried, for the past few years, to write about this habit, and failed. “I . . . some part of me . . . the part of the ‘I’ who bodybuilds . . . was rejecting language, any verbal description of the process of bodybuilding,” she writes in the essay’s brief introduction (ellipses included).

From this inability to write of bodybuilding, Acker deduces that bodybuilding itself is a sort of foreign language of the body, one which turns to a meditative state for the serious bodybuilder. The language is stripped of adverbs and adjectives; it is made of simple and strange nouns (“reps,” “squats,” “sets”) and counting. It is tied up with breathing.

I thought of this essay, which I skimmed once a few years ago while looking for readings to assign on a short unit about “writing the body,” while reading Emma Specter’s recent More, Please this week. (In a cruel twist, I decided to dispense of the body unit in my class and instead talk about writing family members; but for that unit, I chose an excerpt from Carrie Brownstein’s memoir, which includes extensive and harsh writing about her mother’s long battle with anorexia that culminated in an extended stay in an eating disorder unit of a hospital while Brownstein was school aged. I did not put any kind of trigger warning on the reading—not because I didn’t believe in them, but because I’d eschewed reading the piece closely immediately beforehand and figured it would probably be fine. This turned out not to be the case. One student cried, and I am sure I also did, later, when class ended. This is the novice I remain as a teacher, to be clear.) I reread Acker’s essay in the hopes that it might help me confront the question Specter’s book raised for me: Is it possible to capture the experience of physical embodiment? And if so, how?

As the wordy subtitle implies, More, Please is Specter’s story of her lifelong push-and-pull with food, and in particular with binge-eating disorder (BED), but also the story of her life, her relationships, and her work. As I remember it, I heard about the book when it was having its concurrent press cycle with a different book about disordered eating, Emmeline Cline’s Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm. I put on podcasts with each of the writers back-to-back, and by the end decided that Specter’s book sounded more interesting; it went on my list where it festered until last week, when I found it at the library.

Specter’s memoir—like so many written by journalists and media-types—is peppered with interviews with people who have dealt with disordered eating and occupied worlds that interest or overlap with Specter’s, whether they are media personalities and writers, fat activists, or chefs. These interviews provide some dimension or newness, if they also divert attention from the narrative at hand. This is an understandable enough move, to pull away from the hard thing; yet the book opens with the writer in bed after a night out, surrounded by crumbs and grease streaks and sweat stains, and not infrequently returns to the nausea and numbness that follows a binge.

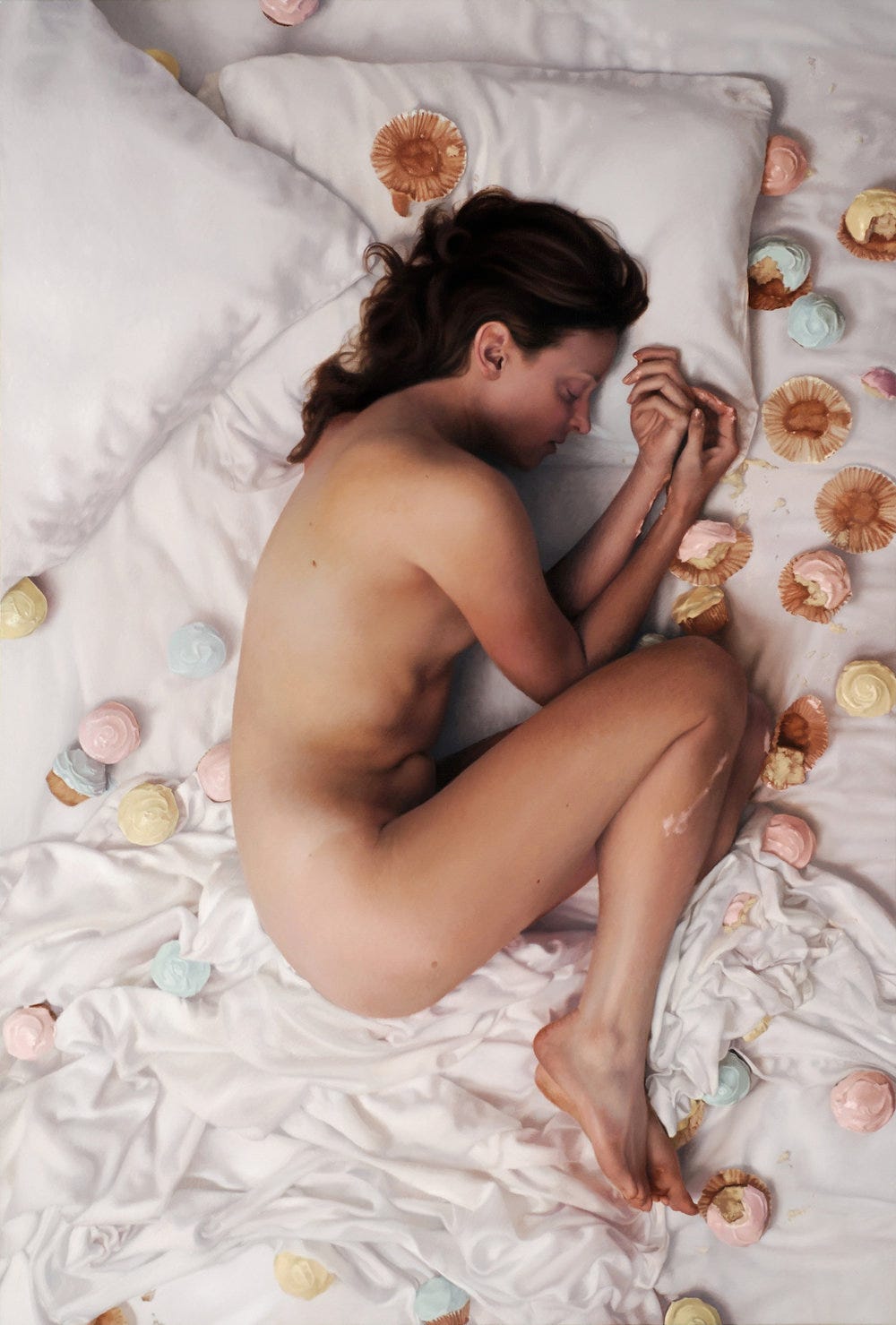

The book ambles through Specter’s life as a media worker, making her way from a childhood lived across the world and in New York City to assistant-type roles in Hollywood and, finally, into a staff role at Vogue. Concurrently she describes her inner world across these phases of life: alternatingly depressed and ostracized, closeted until her mid-twenties and held hostage by her desire to be thin. Along with the interviews, Specter also weaves in relevant art and media that has spoken, in some way, to her illness—books from the seventh grade about anorexia and bulimia, paintings by Lee Price, or TV shows and movies that include some representation of binging or fatness. If this seems like a lot for two hundred pages, I suppose it is. But Specter’s writing is punchy and readable, not unlike the personal essays that pepper web magazines and go viral on a regular basis (including some of Specter’s own, another experience she writes about in the book).

In a brief aside in the middle of that bodybuilding essay, after which she’s stated that she’ll at last be able to “directly talk about” the act, Acker includes a parenthetical: “(As if speech is ever direct.)” It’s a small moment—the two sentences make up their own paragraph—but an important one in the essay, and in thinking about writing about embodiment more generally. That language is simultaneously our main tool for communication and also obscure, distant from the things it attempts to describe is the problem of writing in general, and especially of writing about living in the world in a body, not only in a mind.

I’ve run into this problem in the few times I’ve tried to write anything about my bodily experience—once when I tried to write about my horrible menstrual cycles in college, then again when I tried to write about my sensitive stomach in grad school. In a workshop of the latter, another student circled several passages on a printed draft and annotated them with a question: What does this mean? Whether maliciously or not (this student summarily blocked me on all social media as soon as we graduated, which gives me pause and makes me giggle to this day), she was pointing out the loopy, metaphorical quality of my writing that didn’t hold up to the scrutiny of close thought. It’s rare, I think, to find writing about the body that does. This is why Specter’s work is admirable, even if it fails to “wholly capture” the experience of bingeing or having BED, and it’s why Acker’s essay is brilliant.

Near the end of More, Please, the writer has found love and is beginning to find peace in her body. The reader winds their way to what feels like a happy ending—something which Specter herself admits would be a falsehood. There’s not a miracle cure, nor such a thing as a perfect recovery. On the very last page of the book, Specter confesses that she doesn’t quite know how she has gotten better, writing that “the answer is that there’s not just one answer, as annoyingly mystical as that sentence may sound.”

But this isn’t where the book makes its final landing. Instead, it ends on a different note: Specter realizing that part of what has made her better over time is just growing up. In the very last line, then, the book becomes a memoir in the truest sense; not about one aspect of Specter’s life, but suddenly recast as the story of her life as a whole. This is a smart move, I think, because it distinguishes this book as a singular story—not a self-help diatribe, a work of cultural criticism, or a researched foray into the world of disordered eating. But by becoming the story of her life, More, Please can also encompass each of those genres and modes with ease, despite or maybe because of the fact that language fails Specter and all of us who live in bodies. 🐁