Isolated Data

Shorties 1

This is the first installment of Shorties, a series where I review a short book off my shelf each week for ten weeks. Next week I will read and write about When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut.

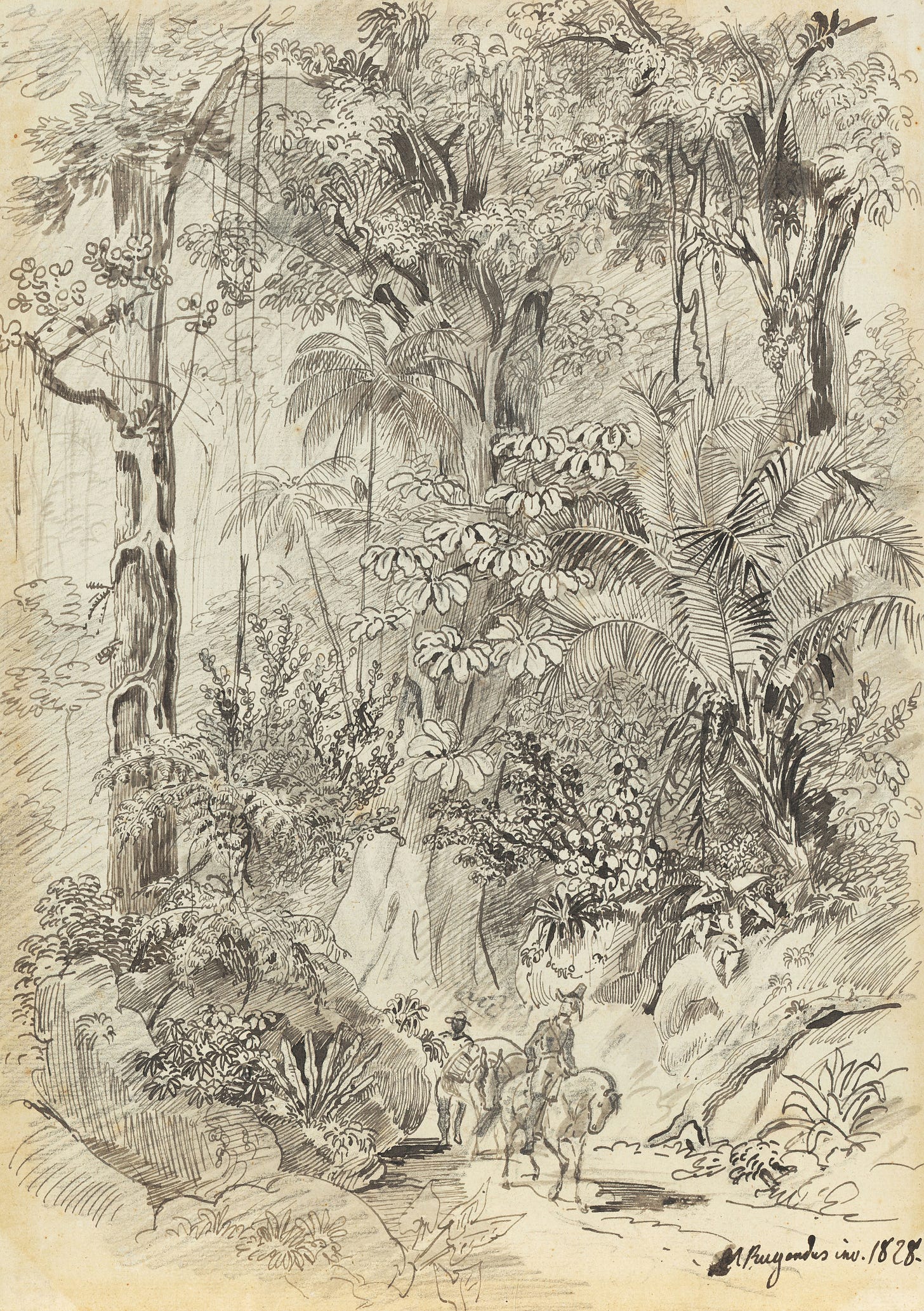

An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter by César Aira. New Directions, 2006. 88 pages.

Somewhere in the middle of An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter—after a climactic accident has left our main character, the German landscape painter Johann Moritz Rugendas, mutilated and partially disabled—the third person narrator reflects on Rugendas’s return to life, and in particular a return to writing his letters. Not only did he have to keep promises made to elaborate on his accident and condition to his sister back in Germany, but he also had to “clarify things for himself and come to terms with the gravity of his situation.” In short, Rugendas needed to self actualize through his letters, to do the work we might now ascribe to a workbook or therapy session about who he was in the wake of his accident. “The artist’s mastery of documentation had carried over to the rest of his life, becoming second nature to the man,” writes our narrator, in neither a positive or negative tone.

By this point in the novel, Rugendas has traveled to and from the Americas once, and he has now returned. His accident, and the apex of the story Aira tells, occurs on a supplementary excursion to Argentina from Chile. Rugendas is fond of, even obsessive over the flatlands, a place that his contemporary Alexander von Humboldt sees no value in painting. To Humboldt, the task of a landscape painter is to capture the “physiognomy of a place”; beyond the literal pieces of a landscape, a master arrangement had the potential to reveal “climate, history, race, fauna, flora, rainfall, prevailing winds” through suggestion. This meant that a natural landscape filled with vegetation would better suit the aesthetic aims of a landscape artist, and in turn that a flatland would have little of value worth documenting.

Still, Rugendas insisted that he and his friend Robert Krause cross over the Andes into Argentina, a place he could not ignore for long. After some days staying with acquaintances in towns, the painters venture out to the flatlands with guides ahead. One and a half days into a hot expanse of stripped land, the men are going hungry, the guide is embarrassed at his failure, and Rugendas decides that he’ll split off from the group towards the distant mountains in search of reprieve. Stubbornly he exits, and the narrator and reader follow him into an expanse growing grey and dark with storm clouds. The mountains in his distant view seem to get smaller, not larger, as he crosses the darkening expanse.

Rugendas is struck by lightning on horseback, twice, then dragged out of the barren lands by his horse, who he’s still attached to by one stirrup. The group finds him alive the next morning with a nerve at the top of his head exposed. In the ensuing weeks and months, his wounds heal, but to detrimental effects: He takes a watered-down opiate to stave off migraines and light sensitivities, and his face is constantly twitching in fits that are uncontrollable and hardly detectable to him but clearly visible to everyone else. This is the state with which Rugendas must urgently contend when he gets back to his writing desk.

“In his work, Rugendas had come to the conclusion that the lines of a drawing should not represent corresponding lines in visible reality,” our narrator writes in the middle of the book, “in a one-to-one equivalence. On the contrary, the line’s function was constructive.” After his accident, Rugendas sees the world more like a Buddhist, a place where each thing has been and will become another and each other. Thus, a piece of art is a construction of something that has existed and will exist while also being singularly itself; “Everything was documentation! . . . There were no pure, isolated data.”

But what is true here? Rugendas, who was a real historical figure, is presented with a vivid internal world, with intentions and hopes, friendships and quirks. Of course he was a full human person. But Aira, through the lens of a frank and direct narrator, is making things up. Johann Moritz Rugendas was a master landscape painter, and he was fond of Argentina. He was not, for all appearances, struck by lightning, much less twice, and he did not live out his life with a disfigured face or debilitating symptoms stemming from such an accident.

The genius of this little book is the sleight of hand with which Aira first inserts then immerses a reader in fictions. One second you are reading verifiable information; the next, you have slipped into narrative territory. By the time you’re reading a fully fictionalized account, you’ve forgotten yourself, both because the story is interesting, and because the detail seems to lend it all some credence. It’s easy to forget that the detail is what should give the story away as false—of course he wasn’t struck by lightning twice, I told Dylan only after I’d finished the book and scanned Rugendas’s Wikipedia.

I was and am stuck on that section of several pages in the middle of the book—about correspondence, self realization, self acceptance, and art—because they so succinctly describe the project of the book itself. I guess this is the other genius of the book, that written in it is a pretty direct set of instructions regarding its themes, which doesn’t appear as particularly heavy-handed or unrendered. This is because it’s filtered through the experience of Rugendas as a character, and plausibly so. The thoughts and questions he has about veracity, about what art does in the world beyond communicating (a) reality, are at stake both in the life of the character of Rugendas, and in Aira’s own work. There are no pure, isolated data. Aira seems to take this as a guiding force; if it’s true, then supplementation, combination might more readily strike at the heart of a story that needs to be told.

In fiction, and in reading about fiction that isn’t autofiction, the issue of truth does not always arise naturally. But here it seems like an essential part of the reading experience (whether during or after, as it was for me). Aira could have just as easily written a fictional character like Rugendas; that he instead wrote a story using the likeness of the real man is a clue that the project of the book is at least partly to consider how truth functions in narrative, and to what degree it can slant and skew a story.

Here is something of a thesis statement, nested almost in the exact middle of An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter: “In the game of repetitions and permutations, [Rugendas] could conceal himself even in his new state, and function unseen like any other avatar of the artist. Repetitions: in other words, the history of art.” Like writing a novel with fragments of the real at the foundation, the character of Rugendas himself understands that a story unfolds over and over. Fictionalization: An act of repetition, a re-up of one story for today, but also for yesterday, and for tomorrow. 🐁