Actually, I Like It

Installment 14: Earnestposting; Arts and Crafts; Sexy Tennis

I have much to report. I wrote this month from planes, trains, automobiles, air mattresses, and couches, traveling multiply for graduations and catch-ups. This installment’s title comes from a bookmark I bought at a museum gift shop (maybe one of the best museum gift shops ever—at the American Visionary Art Museum—which contains a bunch of cool junk bought wholesale and therefore sold cheaply, unlike most museum gift shops which sell cool junk at an offensive markup) which reads, “Baltimore. Actually, I Like It.” I concur with the bookmark and I think it’s cute for a city to know it might seem like it sucks—a more self-aware “Keep Austin Weird.” So: May. Actually, I Liked It.

Because of things like airtime and layovers, I’ve let myself go a bit rogue on this post. This and the fact that I “consumed” so many things worth thinking and writing about with a small room’s worth of people. When I migrated it to Word to work offline it was solidly 1400 words, and I won’t bother to tell you how long it is in final form, as a small mercy to you. Maybe just read until you tire of me this time around.

Watching

There’s a running bit in an episode of Maria Bamford’s Lady Dynamite (at one time one of my favorite ever TV shows) where a very mentally ill Maria, in an attempt to retain her cheery façade, releases her negative energy only in quick moments by screaming into a big yellow sponge in an empty, not-running shower so hard she shakes. It registers as funny, not sad (unlike Kendall Roy’s version).

This was the preeminent image in my mind while watching Challengers in theaters with my friend Weezie in the back row of an AMC this month; that if I was at home, probably every few minutes or so I would be screaming into the sponge. It’s unfair for you all to be subjected to my love of this movie, so rarely perfect in my eyes as to render my reading almost void, which Weezie described beforehand as about “a woman who coaches her husband to be a great tennis player, right?” Yeah, kinda! I love that it’s melodramatic without getting remotely campy, that it’s basically Infinite Jest twice adapted, first into a sexy anime and then again into live action for an American audience. At no point was I particularly surprised, but my attention was held so intensely that I was a little giddy the whole time, truly on the edge of my seat. I’m usually unimpressed by Luca Guadagnino (I hated his useless and excessive remake of Suspiria) and always unimpressed by Zendaya, but her usual affect worked in favor of Tashi Duncan, the distant and cold tennis extraordinaire-would-be she plays. I loosely read the movie as homoerotic—about Art Donaldson and Patrick Zweig’s relationship through and around the woman they’re both chasing to get to each other—though I don’t think it’s meant to be outright gay, or that they are gay for each other. (Not to be annoying, but, erotic as in eros as in deep feeling—the movie isn’t deep, at all, but it evokes that profound feeling that sometimes graces friendships suddenly and forever.) I think it’s about becoming a man and competition and beauty. I also think it’s all in good fun, meant to inspire heart-fluttering and giggling and feeling “in on” something. I don’t think a viewer is meant to feel confused or turned around at any point; instead, everything about the plot is obvious because to have a fun viewing experience, one needs to know exactly what’s happening. (I am very close to making a point about why there’s no sex onscreen, but maybe in the spirit of the movie will neglect to make it final.) The point is fun, beauty, the tease.

(Bearing in mind, also, the meteoric—as in, bright and fast-burning—rise of Mike Faist and Josh O’Connor on my timeline: what happened to Paul Mescal? Has anyone written about how the culture is of late cycling through white boys at breakneck speed? If I was currently the proverbial online teenage girl, would I erect a new poster above the bed of the newest hot guy every couple of weeks? Or are white boys of the week now relegated to 20-plus-year-old women, us who watch the sexless PG-13 movies gripped by the possibility that our next fantasies can thusly include a 4k HD memory of the latest brunette with blue eyes and a great fake American accent? And, from this aside, can you tell I also watched The Idea of You this month—that fangirl fantasy come to life with such seriousness it’s almost impossible not to take it at its face, to suspend disbelief and allow yourself to be awash in the perversity of the projection, a mother who is taken by and takes a Harry Styles doppelgänger in spirit if not body? With each passing day I regret not backing up the ~40 pages of “zine” about One Direction and Tumblr fangirldom I wrote in 2019 in the interim period of my life where I worked at the ice cream shop and the pre-pre-k concurrently. It’s lost in my old laptop, perpetually locked, and I fear it still contains most of my best insights about famous white boys, their allure and grip on us all.)

Initially I’d intended to rave about Challengers for a while longer, and in my original draft I guessed that it would be my favorite movie of the year. That might still hold—but I also saw Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow, a new and serious contender. It’s the second movie of theirs I’ve seen and been totally blown away by. TV Glow was almost indescribably good—so unexpectedly moving and resounding and existentially horrifying. On a plane the day after I saw it, I wrote a long essay about the movie and its ethos, and I’m still trying to figure out if I’ll release it here or try to get it published elsewhere.

For the unfamiliar, the movie follows Owen and Maddie, two kids who meet as young teenagers in the late 90s and bond over their love of The Pink Opaque, a Disney Channel-esque show about two girls who can communicate in the psychic plane, and must do so to save the world from going into Mister Melancholy’s Midnight Realm. When Maddie disappears immediately after the series ends, leaving behind only her TV set on fire, Owen has little reprieve from the world besides the show, which he watches and rewatches as his life passes him by. Metaphors abound—for queerness and the repression of it, for a life unlived, for (if I may be so bold) free will and (un)seized autonomy in the face of the puke-and-shit real world.

The gist of my argument in that as yet unpublished essay: If the millennial affect is characterized by cynicism, irony, and detachment while simultaneously fixating on analog nostalgia (Urban Outfitters record players; last standing video rental stores still stocking VHS tapes; Disney Adults; the list goes on…), Schoenbrun’s entire oeuvre stands as a testament against that affect, earnest to its core. Their work calls up the archival memory of the millennial without relishing or romanticizing it, using stuff of the 90s—The Pink Opaque is blocked exactly in the style of teen dramas of that era, from the main characters’ over-stylized, tie-dye-and-bucket-hat outfits to the grain of the TV to the way they meet, sitting cross-legged across from one another on a pier overlooking a mirrory lake—as set pieces that evoke without insisting. That the worlds Schoenbrun builds are so wholly realized both by their own visual language (dark purple-y scenes punctuated by neon) and those of the time period they’re writing about makes them easy to settle into, which in turn makes the emotional resonance of their work sneaky. You feel comfortable in the suggestion of an image, then betrayed when it rears its horrifying, monstrous face. You feel you might be in a sweet coming of age story before realizing you’re trapped in suspended adolescence, a regrettably arrested development that can only communicate with sorry, sorry, I wish I was different, sorry.

Schoenbrun’s movies are slow burns, punchy at the end. They operate in contrast to what one expects from a straight-up horror flick, not relying necessarily on suspense or jump scares or some big explanatory reveal. In the case of TV Glow, the ultimate message is stupidly, maddeningly simple—one must be oneself, even when it’s scary. This “moral” is functionally the same as most Pixar movies. And yet. I recommend this movie with so many stars, and for everyone, everywhere, immediately.

Reading

As a continuation of TV Glow talk, I really recommend Grace Byron’s essay in Mubi Notebook about the movie, which situates it beautifully among other films and theorists and thinkers. I had “the archive” loosely in mind before I read her piece, but her use of the idea frankly blows mine out of the water. (For everything I have to say about the movie, I do think trans critics have the most reliable reads on it, as it is a trans story and the metaphors that dominate the narrative are about transness.)

I also read Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, which I really liked—I found it really readable and quippy and quirky, and I liked that it was a murder mystery without the trappings of a more classic one. Couched in the narration of middle-aged Janina, who is obsessed with animal rights and deep astrology and spying on her distant neighbors, it’s gorgeously bleak, set over the course of a few seasons in rural Poland. Janina is a house-sitter for her neighbors’ summer homes, friends with hardly anyone, and judgmental to the point of absurdity. This novel stood directly opposite of the two American first-person novels I read earlier this year (Miranda July’s All Fours and Raven Lelani’s Luster), self-aware without aggrandizing, internal without a lot of navel gazing.

Listening

I’m spending a lot of time listening to Sweet Trip’s 2003 Velocity: Design: Comfort, an album I didn’t pay much attention to when I first got into them and their 2009 You Will Never Know Why. It’s not clear to me why my tastes change like that—I used to think Velocity was too noisy, but lately I love that quality, and find it relaxing and encompassing. In truth, the two albums bear a lot of similarities to each other; I always think of “Sept,” from the former, as being on the latter album. I’ve especially listened to “Dedicated” on repeat, am totally entranced by it and the entire album’s mystical lyrics (“I know you too well to bring out ten” is one of three lines in the song—what does it mean? How many times do I have to listen to the song before I understand?). How did two people make this and know it would sound good?

I’ve also been watching through many iterations of Alvvays’s live performances on YouTube, including their Tiny Desk and both of their KEXP sets. I’m partial to the newer stuff on account of the fact that they always play “Belinda Says,” just a kicker of a song with the best opening lines (“Can’t explain my ankle sprain / I didn’t really feel it”). Their more recent KEXP set introduced me to this cover of “Pharmacist” by Jeff Tweedy, which I note here for my loyal reader and friend Ronnie in case she hasn’t heard it yet. (I also, for the record, watch all of these for the hot drummer.)

And, yeah, I’ve been listening to the new A.G. Cook. Lots of it is decent, but let’s be real—he’s no SOPHIE, no one is no SOPHIE, there’s never gonna be another SOPHIE. I’m coming around to the A.G. produced Charli XCX singles with this in mind, that this is what hyperpop is now, post-Covid, post-SOPHIE, post-Shien influencer retreat. Everything’s a little cheap, predestined to be of the moment and this moment only.

On View

Over the course of my ten-day trip around the northeast—first Baltimore, then DC, and finally Boston—I visited, I think, six museums, most of them art museums. Hence this new and probably not lasting section on visual art. If you’re still reading I feel like I should be paying you. Of note:

Janet Echelman’s 1.8 Renwick, on display at the Renwick Gallery in DC. It’s hard to get a good photo of this piece, which spans a massive ballroom-type space with probably 20+ foot high ceilings. It consists, to my mind, of three elements: netting, suspended from the ceiling at multiple points to create a topographic form which one views from below, as though standing behind the surface of a map; a carpet, printed with the topographic information of the netting above; and lights which project onto the netting and color the entire room, cycling through bright gradients that start almost neon and climax in a very intense red. The piece uses the topographic map of a massive earthquake which shifted the Earth’s axis such that each day subsequently became 1/8th of a second shorter. To watch the entire thing takes about the duration of a real sunset, which makes the piece feel monumental; from a plane home, looking down at a small mountain range, I recognized that it really was a remarkable work to be situated essentially inside and far beyond a map of an event, a moment of such gravity as to change the course of our everyday lives. I was moved, as was my entire family, and as all of us are varying degrees of not-really-visual-arts-people, I consider this a testament to how great the piece really is.

Though I won’t write about the National Museum of African American History and Culture as a whole—I neither viewed it in its entirety, nor want to write about history so much as art here—one facet of it strikes me as worth mentioning: the room called the Contemplative Court at the end of the main exhibition. It took me and my family 2.5 hours to get through that part, which is the part everyone goes for, which walks a visitor from the beginnings of slavery in the US through to the present day across three floors. I think it goes without saying that the museum is a serious undertaking—both in the sense that it’s a lot of walking, reading, and focusing for someone who intends to really learn or experience anything there, and also that the information depicted is grave. Outside of the entrance of the museum, a cylinder with small windows protrudes from the ground, and there’s space for people to sit outside in the shade before going in. Only when one gets to the end of the main exhibit does one understand what that cylinder is: the fixture which gives light and shape to an indoor fountain at the center of a room where visitors are invited to recharge and reflect at the end of their visit. It’s a cold, marble room, but not sterile so much as it’s intentionally refined; the fountain, lit seemingly exclusively by natural light from where visitors sit at ground-level, splashes mist towards two long, black, marble benches where people sit quietly and watch water hit water. It’s fantastic—such an incitement to thoughtfulness, a last effort to impart on a visitor that to feel stricken, to feel a bad feeling, at the end of the main course is appropriate and expected.

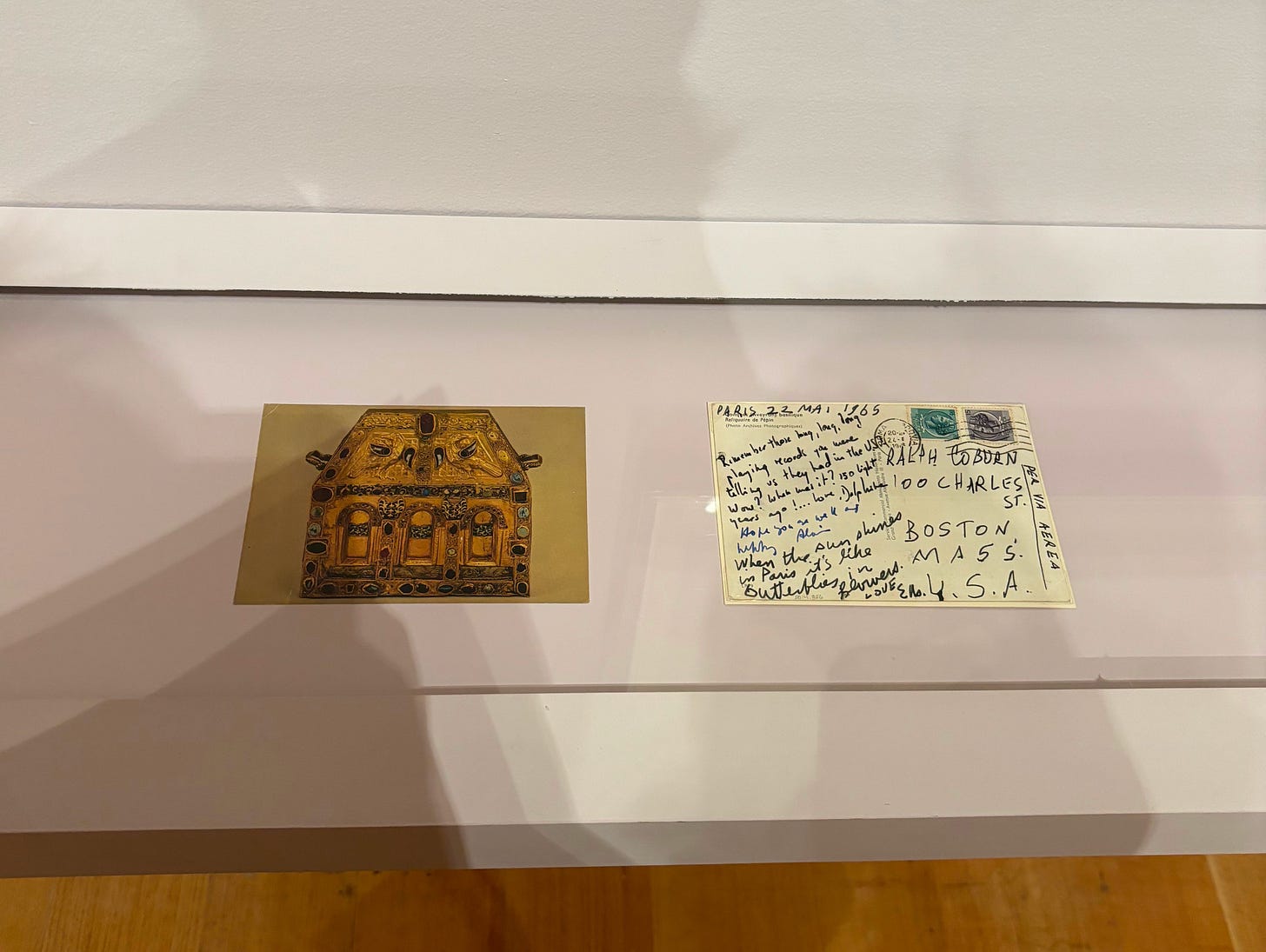

In Boston’s Museum of Fine Art, an exhibit called “Tender Loving Care” stood out, perhaps because I deliberately angled for the contemporary wing above all others, and because it was so sprawling, organized like a long essay or an index. I guess I’m thinking about it because of the structure; rather than reading about the pieces on a little placard on the wall, visitors were encouraged either to take a battered paper book of information, or scan a QR code of the guide and follow along on their phone. The accents were pink or orange (including walls), and the exhibit was also populated by seating that was made by artists who had work at the MFA, a program called Please, Take a Seat! Of course, I felt compelled to sit on every possible art-object, and with the exhibition encompassing the length of the second level of the museum, it felt impossible to read about even a third of the pieces, which skewed towards women artists and craft pieces. It seemed only loosely principled, kind of a vibes-based exhibition. One piece was a postcard—just a postcard. I thought of my life.

(More generally I’m interested in the movement I apparently witnessed across multiple museums in multiple cities that prioritized craft as the feature of their exhibitions. This in contrast, I assume, to an exhibit of straight up art, stuff made for the sake of being aesthetically beautiful. If I’m making assumptions this looks to be a reaction to the past several years of changing social discourse about women, power, and legitimacy. But it’s a little awkward if that is what’s happening, as it inadvertently poses craftsmen—whether they’re “untrained” e.g. hobbyists or folk artists, or women working in less respected or established mediums—as other to fine artists. The distinction between arts and crafts is certainly historical, but I guess I mostly wonder why it still needs to be so strictly upheld.)

Ok that’s enough. Not to engagement bait but please comment below what kind of summer you’re having—no “hot girl summers” allowed. Love u. 🐁

i’m having a jude law summer 🎉

As a bad consumer - I find your takes on celebrity names I don’t recognize comforting. Im having an album on-repeat tinned fish charcuterie mug making summer